There is a lot of vaping-related law reform activity going on in Australia at the moment. This (long) post reviews NSW vaping laws and provides a baseline for understanding the changes that are underway, both at NSW (State) and Commonwealth level.

Background

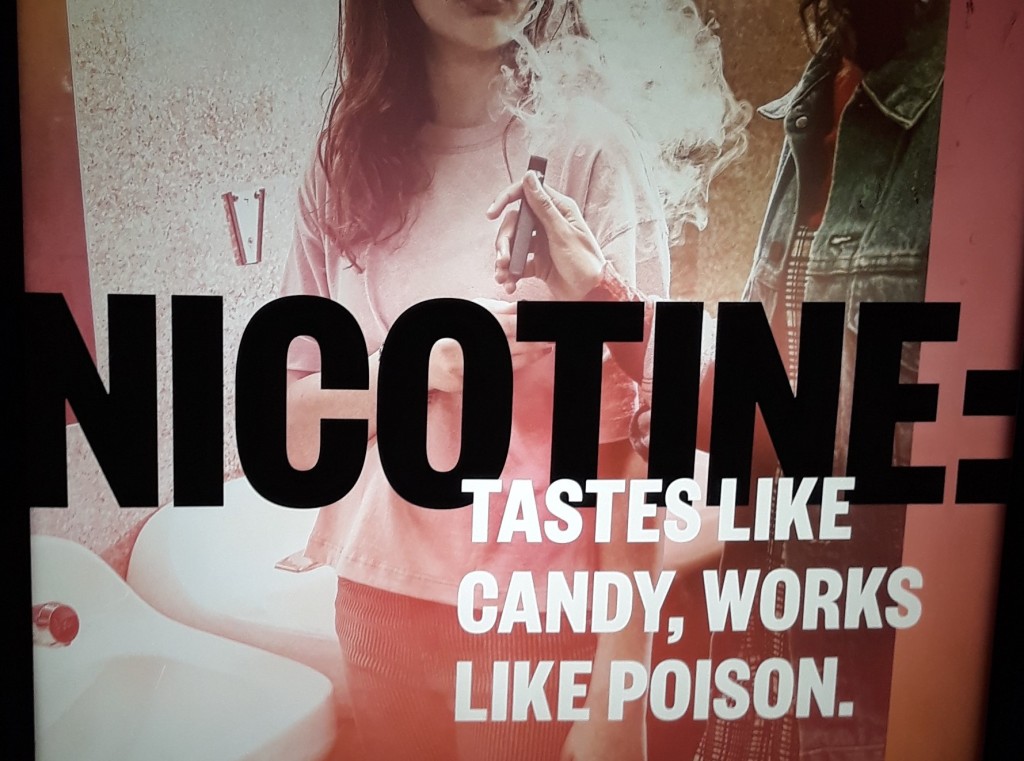

The failure to enforce nicotine control laws, together with ludicrously low penalties, have helped to created a black market and a surge in vaping rates in Australia, predominantly in children, teenagers and young people: see here, here, and here.

Current vaping in 14-17 year olds rose from around 2% in 2020 to 14.5% in the first quarter of 2023.

For 18-24 year olds, current vaping rose from 5.6% to 19.8% over the same period (Source: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria). For other reports, see here, here, here, and here.

As a culture of vaping has evolved, reports have emerged of children as young as four vaping. Accidental vaping exposures, including nicotine poisoning in toddlers, have also risen.

Health Minister Mark Butler MP told the National Press Club in May: “Vaping has become the number one behavioural issue in high schools. And it’s becoming widespread in primary schools.” See also here, here, here, and here.

E-cigarette advocates, meanwhile, are openly advocating for schools to tolerate vaping among students.

One argues that schools should designate an outdoor vaping area for students, and that students should be permitted to “take short breaks to vape outside if needed during class hours.”

See here for the World Health Organisation’s recommendations on nicotine- and tobacco-free schools.

So…what’s needed to clean up the mess? “Concerted, comprehensive action by all levels of government”, according to the Minister.

Commonwealth regulation of nicotine

Nicotine, a poison, is regulated in the Poisons Acts of the States and Territories, which are based on a federal standard called the Poisons Standard.

The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) Part 6-3 sets out the administrative machinery for the creation and regular updating of the Poisons Standard by the Secretary.

The classification of poisons into the various Schedules of the Poisons Standard represents recommendations to the States and Territories, since the regulatory controls themselves are implemented through State and Territory poisons legislation.

Schedule 4 of the Poisons Standard lists poisons that are prescription-only medicines (or prescription animal remedies). Under Schedule 4, nicotine is scheduled as a prescription-only medicine, except when it takes the form of nasal spray or nicotine patches, or when it is prepared and packed for smoking.

This classification decision, which dates from 1 October 2021, was intended to capture all nicotine vaping products as prescription only medicines. (Prior to that time, it was still possible for an individual to import nicotine vaping products for personal use without a prescription).

Australia has not encouraged the entry of new forms of recreational nicotine onto the market, even though such products would be highly profitable for convenience stores and other retailers.

In summary, except when nicotine takes the form of a combustible, recreational tobacco product (such as cigarettes, which are regulated by tobacco control laws), or when it takes the form of a quit smoking aid, nicotine is a prescription-only medicine.

Current regulation of nicotine in New South Wales

The Poisons Standard is implemented under State and Territory poisons laws. In NSW, this is currently the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 (NSW) and the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 (NSW).

The 1966 Act defines a “restricted substance” as a substance specified in Schedule 4 of the NSW Poisons List. The NSW Poisons List is the same as the Poisons Standard (see s 4, definition of “restricted substance”, in the Act).

More generally, the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 (NSW) states that the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth), and all regulations and orders made under it, as amended from time to time, apply in NSW (see ss 31-31D).

Part 3 of the 1966 Act, and Part 3 of the 2008 Regulation contain detailed requirements (and offences) that relate to “restricted substances”. For example, s 33 of the Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 (NSW) states that a medical practitioner may not issue a prescription for a restricted substance “otherwise than for medical treatment” (s 33).

This goes to the heart of the debate about vaping. In contrast to the UK, where the government promotes vaping in the hope that it will reduce smoking rates, Australia has been cautious about promoting addictive products containing toxic chemicals to smokers (see here, here and here).

Australian law frames nicotine use as an addiction. It doesn’t validate addiction by treating nicotine vapes as benign recreational drug-taking. It doesn’t prohibit nicotine vapes either – let’s put misrepresentations by vaping advocates aside. It authorises nicotine e-cigarette prescriptions as a form of treatment to support smoking cessation or to manage nicotine withdrawal symptoms, but not as a first-line therapy.

By taking this cautious middle ground, Australia’s regulatory model seeks to avoid perpetuating inter-generational nicotine addiction through new forms of recreational nicotine use. This is something that many people care about deeply. Just ask a parent.

It’s a worthy goal, but one that will slip away unless governments take enforcement seriously.

Section 10(3) of the 1966 Act is a key offence provision that would apply to a retailer who sold nicotine vapes to a person who didn’t have a prescription. It provides that: “A person who supplies a restricted substance otherwise than by wholesale is guilty of an offence.”

There are a number of exceptions, including when a nicotine e-cigarette is supplied on prescription by a pharmacist, or by a medical practitioner in the lawful practice of his or her profession.

The 1966 Act is badly out of date, and the penalties for offences under the Act are ludicrous in light of the economic incentives to supply nicotine vapes on the black market.

The maximum fine for an offence under s 10(3) is $1650. Most offences, if prosecuted, would attract fines of far less than the maximum.

It seems likely that the absence of genuine penalties for non-compliance with poisons laws has encouraged the continued illegal sale of nicotine vaping products by retailers. And if you’re happy to sell illegal vapes, why bother to only sell them to adults?

The States are in the process of clarifying and updating poisons laws governing vaping products. The NSW Parliament has passed the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2022 (NSW), but it has not yet commenced operation, pending community consultation on draft Regulations. This post discusses the current legislation.

Obtaining nicotine vaping products under prescription

The classification of nicotine as a prescription-only medicine is important. The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) states that:

“Generally, prescription medicines must be approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and registered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) before they can be lawfully imported into, or supplied in, Australia.”

This is reflected in offence provisions in the States & Territories. For example, in NSW (in addition to offences relating to “restricted substances”, noted above), it is an offence to supply therapeutic goods to a person by retail unless the goods are registered or listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods or are exempt goods (1966 Act, s 36A). The ARTG is a database of therapeutic goods, including prescription medicines, that can be lawfully supplied in Australia.

The TGA points out that it has not yet approved any nicotine vaping products on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods.

Despite this, nicotine e-cigarettes can be accessed in Australia as “unapproved medicines”, with a doctor’s prescription. There are three special access pathways that currently apply.

Firstly, individuals can personally import up to 3 months’ supply of e-cigarettes and vaping liquids, provided they have a doctor’s prescription: see here, and here.

Secondly, under the Authorised Prescriber Scheme, doctors can supply unapproved medicines (therapeutic goods not included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods) to a class of patients with a particular medical condition.

And thirdly, the Special Access Scheme allows doctors to supply unapproved medicines to a specific patient.

Under both schemes, the patient would fill their prescription at a pharmacy.

Commonwealth law seeks to control the quality of vaping products supplied under these special access schemes.

Although e-cigarettes are not registered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods, the TGA has released a federal standard (known as “TGO 110”) that applies to nicotine vaping products obtained on prescription.

TGO 110 applies to “nicotine vaping products that are imported into, manufactured or supplied in, or exported from, Australia”.

The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 Chapter 5 regulates the advertising of therapeutic goods. Advertisers are also subject to the Therapeutic Goods Advertising Code issued by the Minister (s 42BAA).

Under s 42K, the Secretary can authorise specific representations in advertisements about specified therapeutic products, and this has been done in relation to advising the public of the availability of nicotine prescriptions.

Commonwealth nicotine and vaping law reforms

The Therapeutic Goods Administration is seeking comments on proposed changes to the pathways for accessing nicotine vaping products (see especially pp 6-7, 12-13).

Under the TGA’s preferred options, it is likely that the personal importation exemption will be removed, in order to prevent this scheme being abused to import vaping products for the black market (see pp 14-15).

Also, an import permit may be required, and would only be granted for products that met enhanced regulatory requirements, as set by the TGA (pp 15-16).

The TGA has foreshadowed new minimum quality and safety standards for nicotine vaping products, essentially expanding the controls in TGO 110. The TGA’s Consultation paper foreshadows the following controls (see pp 19-23):

“2. Prohibit all flavours (except tobacco) and additional ingredients.

3. Modify labelling or packaging requirements, including to require pharmaceutical-like plain packaging and/or additional warning statements.

4. Reduce the maximum nicotine concentration for both freebase nicotine and nicotine salt products to 20 mg/mL (base form or base form equivalent).

5. Limit the maximum volume of liquid [nicotine vaping products] NVPs.

6. Remove access to disposable NVPs.”

Banning disposable vapes is a no-brainer on environmental grounds, let alone health grounds. Plenty of vapers, like many smokers, fail to dispose of their trash responsibly.

The reform of nicotine vaping laws is complicated by the fact that the Commonwealth is also in the process of strengthening Commonwealth tobacco control laws that apply to combustible products, while extending some of these controls to vaping products.

For example, the main Commonwealth Act governing tobacco advertising, the Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act 1992 (Cth) (TAPA Act), doesn’t currently apply to e-cigarette advertising. The proposed Public Health (Tobacco and Other Products) Bill 2023 would rectify this.

It would also consolidate the TAPA Act, and the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) into a single Act – the Public Health (Tobacco and Other Products) Act. See here for further information.

Summary

Combustible tobacco products such as cigarettes are regulated under tobacco control legislation, at State/Territory and Commonwealth levels.

In NSW, tobacco control laws also apply to both nicotine and non-nicotine vaping products. These controls are separate to the nicotine control laws discussed in this post.

State and Territory poisons laws are ill-equipped to deal with the rapid emergence of a black market for nicotine vapes.

Failure to legislate and enforce genuine penalties for black market sales essentially makes compliance with the law optional, leading to higher rates of vaping among teenagers and young people.

In countries that have intentionally taken a softer approach to nicotine regulation, rising vaping rates are also evident, especially among disadvantaged communities.

In New Zealand, daily vaping rates among Māori Year 10 students rose from 19.1% in 2021 to 21.7% in 2022 (and from 21.3% to 25.2% in Māori girls).

It’s almost unbelievable. Twenty-five percent of 15-16 year-old Māori girls vaping daily. And that’s OK? This is the model we ought to be following?

In the UK, where (according to ASH UK) 20.5% of children have tried vaping (2023), up from 15.8% in 2022, one physician writes:

“It is something I observe each day. I take public transport to work and then walk through a socially deprived area. Each day I see children vaping. Not just 15 year olds showing off to their peers but 8, 9, 10 year olds walking to school vaping. I see these children freely vaping on public transport. I see littered plastic and lithium batteries in every street, washed into gutters and then into drains.”

“The justification for e-cigarettes—that they are a prove[n] way for some smokers to quit—seems to have been subverted to something very different.”

Leave a comment